about the tour

Explore a new side to San Diego’s beloved Balboa Park with a self guided tour of the park. This outdoor excursion will help discover some of the park’s tightly-packed history and highlight its landscape design and architecture. The tour also celebrates the designers and other significant people who have contributed to the park’s design history. Due to the size of Balboa Park, this tour will be split into three segments based on the park’s geographic areas — West Mesa, Central Mesa, and East Mesa. Enjoy these self-guided tours one at a time or combine all three into a single trip. Participants are encouraged to bring a picnic and bask in the beauty of one of the most unique public urban parks in the country.

Also Visit:

Public Spaces by Design: Balboa Park West

Public Spaces by Design: Balboa Park East

Photos by Calvin Woo and Susan Merritt

_________________________________________

Central Mesa, the park’s cultural core

The Central Mesa is bound by Upas Street on the north and Interstate 5 on the south and rises up from Cabrillo Canyon on the west and looks out over Florida Canyon on the east. The densest portion of the park, the Central Mesa was the site of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, the 1935 California-Pacific International Exposition, and is now home to 17 museums and cultural institutions. The best way to explore the Central Mesa with an eye on design is to have a look at some of the architectural and landscape design highlights of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition and the 1935 California-Pacific Exposition; as well as several individual examples that have been incorporated into Balboa Park over the years.

The Cabrillo Bridge connects the West Mesa to the Central Mesa so let’s start at Sefton Plaza and walk across the bridge.

Bring a picnic or pick up lunch in the park

Pack your lunch or order takeout from two top-notch restaurants located in the heart of the Central Mesa. If they’re open, enjoy outdoor dining on their patios.

Panama 66 is situated in the May S. Marcy outdoor sculpture courtyard of the San Diego Museum of Art and serves an assortment of casual fare that pairs well with locally-brewed craft beer. Grab & Go is open 11:00–4:00 daily and at the time of this writing Panama 66 was just beginning to offer limited dine-in from 11:00–3:00 daily.

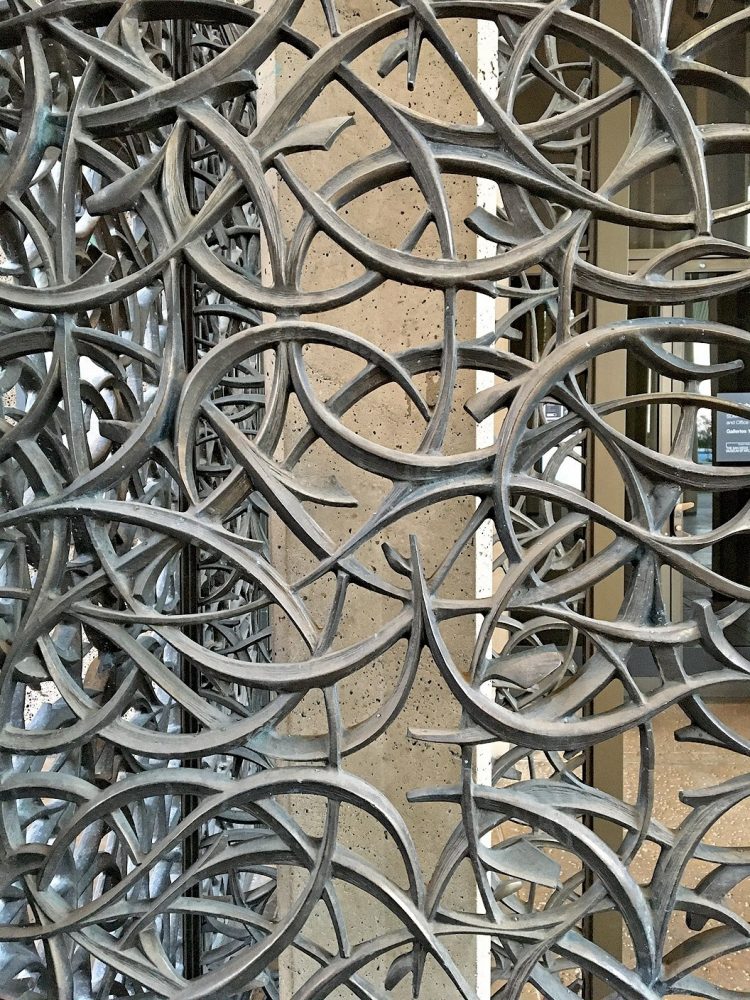

Don’t miss the Leland Malcolm gates!

On your way into the sculpture courtyard be sure to have a look at the stunning 8-foot tall anodized cast-aluminum gates designed in 1966 by architectural sculptor Malcolm Leland.

Leland explained in a 1963 article in Arts and Architecture that architects at the time were using aluminum mainly in sheets or extruded form. He was curious if casting aluminum would allow for more complex and subtle contours and surface textures that weren’t achievable with these other methods. So, he devoted two-and-a-half years to researching and studying contemporary foundry practices, then experimented with designing bas-relief sculptures in modeling sand and casting his designs in aluminum. Where one-of-a-kind casting was required, he found this technique to be simple and economical and maintain a constant thickness of between ¼- to 3/8-inch.

Leland treated the cast surface with an anodize that had been developed for the aircraft industry. Oxidation, he said, “forms a coating that literally grows into the metal, resulting in a much thicker abrasion- and corrosion-resistant surface than the more common anodic coatings.” He claimed the anodized, cast aluminum surface to be harder, denser, maintenance-free, and color-fast.

The strength, durability, and beauty in the intricate interlacing of the museum gates is testament to Leland’s efforts to cultivate a new approach to designing with an existing material. Learn more about the gates and Leland’s contribution to the courtyard’s unique supporting columns in this ArtStop video with James Grebl, Ph.D., manager of the museum’s library and archives.

You’ll also notice extra gate panels mounted to Panama 66’s bar-on-wheels. When graphic designer Jeff Motch, who runs the restaurant with his partners, learned that extra gate panels, which were originally installed on the west side of the courtyard were in storage, he got permission from the museum to integrate several of Leland’s panels into the restaurant decor with the help of designer Jonathon Stevens and metal fabricator Ty Meservy. (San Diego City Beat)

The Prado offers a wide selection of sandwiches and salads that would make for a delicious picnic. If you dine-in they serve a yummy complimentary starter of house-made crackers and hummus with a gentle kick. They also put on a festive happy hour. Ask about their special cocktail designed by their mixologist as a tribute to the first-ever San Diego Design Week (SDDW).

Aptly located in the House of Hospitality, visitors are greeted to The Prado by the soothing sound of splashing water emanating from Donal Hord’s 1935 sculpture, “Woman of Tehuantepec,” centered in the courtyard’s colorful tile fountain. This piece was supported by the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a Federal program that hired artists and designers who were out of work due to the Great Depression to design works for public spaces. The Spanish-Colonial courtyard is attributed to architect Richard Requa. As lead architect for the 1935 California-Pacific Exposition, he reconfigured the 1915 building to turn it into the main visitor’s center.

Save room for dessert!

After your park excursion, stop by either the Bankers Hill or Little Italy location of Extraordinary Desserts, which, believe me, lives up to its name. On Thursday, September 10, and Friday, September 11, mention San Diego Design Week and get 20% off one of the featured Pavlova desserts, a crisp baked meringue filled with Devonshire cream and fresh berries. Both locations were designed by the extraordinary architect Jennifer Luce of LUCE et Studio who will discuss her collaboration with owner and extraordinary pastry chef Karen Krasne in The Architecture of the Pavlova during SDDW.

Now that food is out of the way, and you’ve gotten an introduction to design in the park, let’s begin our tour.

Meet at Sefton Plaza

Directions:

The Cabrillo Bridge connects the West Mesa to the Central Mesa so let’s start at Sefton Plaza on the West Mesa where Balboa Drive intersects El Prado and walk across the bridge. This is the most dramatic and memorable approach to the Central Mesa. During the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, ticket booths stretched between the two gatehouses to welcome visitors to the extravaganza. Historical restoration of the gatehouses was completed in 2017 by Friends of Balboa Park. The decorative caps on top of the gatehouses preview the abundantly ornate Spanish-Colonial architecture that awaits on the other side of the bridge.

You’ll find an interpretive sign in the southeast corner of Sefton Plaza that describes the history of the bridge. Descriptive text and a map of interpretive sign locations is available on the website of the Friends of Balboa Park. Signs like this one are scattered throughout the Central Mesa, all of which are based on a comprehensive sign system developed by Stuart White Design and adopted by the City of San Diego in 1992. RSM Design of San Clemente has been working over the past couple of years in collaboration with the Balboa Park Conservancy on an update to this system, but to the best of my knowledge at the time of this writing none of the new signs has been installed.

Renaming the park: peeling back a layer of history

Before we bridge the West and Central Mesas, now is a good time to talk about the crossover from the original name, City Park, to its current name, Balboa Park, as researched and revealed by Professor Nancy Carol Carter in “Naming Balboa Park: Correcting the Record.” This might be of special interest to designers whose practice includes coming up with names for places, products, and events.

If you’re not from California, a very brief summary might help provide some historical context. In 1835, the Mexican government granted San Diego pueblo status and bestowed upon it 48,500 acres of public lands. In 1848, at the end of the Mexican-American War, Mexico ceded California to the United States and on September 9, 1850, California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state—a free state, that is to say a state in which slavery was illegal.

In 1868, a little over three years after the end of the Civil War, the Board of Trustees of the City of San Diego led by board president José Guadalupe Estudillo and trustees Ephraim Morse and Alonzo Horton, set aside 1400 acres of San Diego’s pueblo land as a public park, which they simply called City Park—straightforward, yet somewhat ironic, since the population at the time was only around 2,300. Hardly a city. The designated tract was nothing more than a dusty, rocky plot of arid land covered with chaparral and wild flowers. No trees in sight. Hardly a park. In spite of its condition, San Diego’s visionary leaders persevered for years until the potential they envisioned for the rugged canyons and mesas was realized. Among them, Horton, Morse, George Marston, and Kate Sessions whose commemorative statues overlook Sefton Plaza on the West Mesa.

Forty-two years after City Park was designated, as San Diego anticipated the 1915 Panama-California Exposition to be held in the park, it was decided that the name City Park was too generic and that a more relevant and prestigious name was needed. The responsibility for renaming the park fell to a three-member park commission: Thomas O’Halloran, Moses A. Luce, and Leroy A. Wright. After delaying their decision for months in the midst of a citywide public debate stoked by The Sun newspaper, the commission announced their decision. The new name was to be Balboa Park after the Spanish explorer, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, who after having climbed to the top of Panama’s Darién peak in 1513 was the first European to see the Pacific Ocean, which the Panama Canal would soon connect to the Atlantic, the occasion that the exposition was celebrating.

Other proposed monikers ran the gamut from names honoring presidents and individuals, like Grant, Washington, Marston, Junípero Serra, and Cabrillo, to more descriptive names related to the environs, such as Sunset, Miramar, Buena Vista, Exposition, and Del Mar. Panama Park was suggested. So was Silver Gate, the unofficial nickname of San Diego Bay, which also referenced San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. It was pointed out, however, that Silver Gate Park made San Diego appear subordinate to San Francisco.

At least some considered Balboa Park a fitting name for the site of a planned year-long celebration dedicated to the opening of the Panama Canal. The event was also intended to shine a spotlight on San Diego as the nearest U.S. port-of-call for ships traveling through the canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It would be good for business and a boom for tourism. Indeed, the exposition was such a success that it was extended for a second year.

“The land divided—the world united—San Diego—the first port of call.” (Headline from San Diego Union, January 1, 1915)

Exposition site moves and Olmsted Brothers yield to Carleton Winslow

The original site for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition was closer to downtown near San Diego High School. The Olmsted Brothers (Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the son, and John Charles Olmsted, the nephew and adopted son of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.), landscape architects from Brookline, Massachusetts, were hired to design the layout of the exposition grounds but when plans changed and the exposition site was moved to the highly-visible center of City Park, the Olmsted Brothers resigned. They felt that the new location would spoil the rural character of the park as designed by Samuel Parsons. The Olmsted Brothers were replaced by Carleton M. Winslow of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s office in New York. Goodhue had been chosen as the architect for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition.

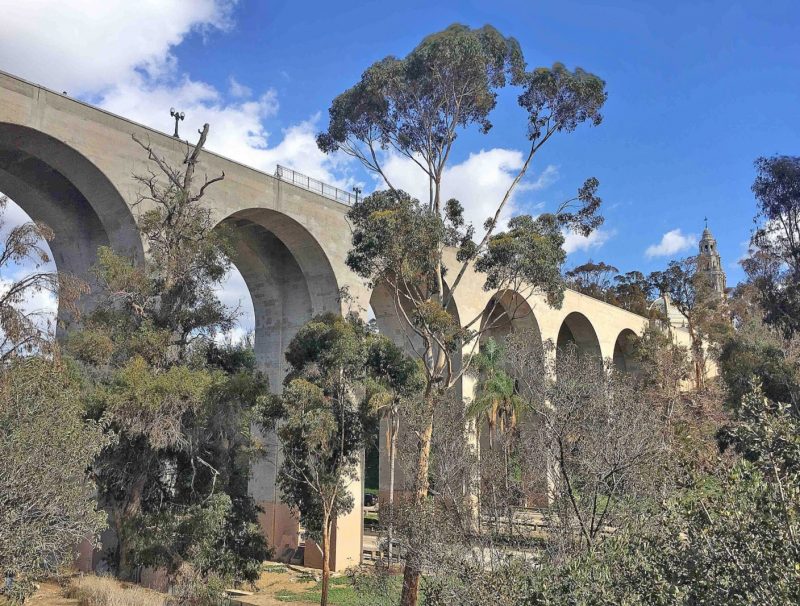

Bridging the mesas

The new location presented the challenge of how to get people across the canyon from the western entry point. Frank P. Allen, Jr., exposition director of works, suggested a bridge. Goodhue drew sketches for a roman-style aqueduct with three repeating arches inspired by the Alcántara Bridge in Toledo, Spain. Allen reached out to Thomas Benton Hunter, Jr., a San Francisco engineer, and came up with the final design, which is the seven-arched bridge you see today. This multi-arched cantilever structure was the first design of its kind in California.

The Cabrillo Bridge was yet another fitting metaphor for that which the exposition aimed to commemorate—bridging the Atlantic and Pacific by way of the Panama Canal.

Now, let’s take a walk on the bridge

“This, the best first view of the Fair, gives one the impression of a city of Spanish romance, with pearl gray walls and towers and flashes of color from tile domes and roofs, set in vivid green of the wooded canyon slopes,” wrote Winslow of the west approach across the Cabrillo Bridge in The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition.

While the bridge is also a road, I recommend walking the 450-foot span; or 916 feet including the approaches. Huge pots (that deserve larger plants) mark the beginning of the actual bridge. As you walk, absorb the significance of this architectural and engineering feat. Take in the panoramic view and imagine when there was no traffic noise rising 120-feet from Highway 163, which at the time of the exposition was an unpaved road called Camino Cabrillo running alongside a man-made lake that reflected the lofty bridge. As you approach the west gate in front of the impressive tower and dome take solace in the fact that the bridge was restored and retrofitted in 2014.

Lamps on the bridge: design in the details

Thirty-one original cast iron double-lamps stand at attention like sentinels keeping watch. Restoration of the lamps was completed in December 2016. Electrical wiring was updated, LED light bulbs were installed, and the standards were freshly powder coated in the historically-accurate green color. The decorative organic motifs just above the manufacturer’s name on the base—Standard Iron Works San Diego California—are an appropriate choice for a park. The 4-point compass rose high up between the two lamps ties in with the repeating 8-point compass rose (starburst) adorning the dome of the California Building at the east end of the bridge. It looks like two facing birds flank the top point of the lamp’s compass rose. I’d like to learn more about these motifs. Were the lamp standards custom designed for the exposition or are they stock pieces from a catalog?

1915 Panama-California Exposition

West Gate iconography

The iconography above the monumental west gate is an interpretation of the official seal of the City of San Diego, which was actually designed by architect Carleton Winslow in response to an open call for submissions in 1913. His graphic design was adopted by the City on April 15, 1914 (discrepancies and all according to city records) and incorporated into the architecture of the west gate with some liberties taken. Most noticeably, the two connected dolphins on the seal, which symbolize the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans united by the Panama Canal, have been replaced by sculptor Furio Piccirilli’s female (Mare Pacificum) and male (Mare Atlanticum) figures, each holding a vessel spilling over with water. Ribbon-like motifs wrapped around the two columns on either side of the shield above present San Diego’s motto Semper Vigilans, “Always Vigilant.” The date 1915 is memorialized above the gateway to the exposition that celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal and all of the benefits that the shortened distance between the two oceans would bring.

1915 Panama-California Exposition theme

The front page of the San Diego Union, January 1, 1915 recounts the exuberance and fantastical impression “the magic city on the hills” left on visitors: “San Diego’s matchless triumph complete when President Wilson presses button which opens fair; loyal Californians, amid enchanted scenes bathed in light, cheer wonder wrought by art, love, and labor; thousands pour into fairyland where old world blends with new.”

The “old world” was represented by the architectural styles chosen by Goodhue and overall staging of the buildings. The “new” was revealed through displays and demonstrations that reinforced the exposition theme—opportunity—predicated by the opening of the Panama Canal.

Concept behind the 1915 architecture

Goodhue explained his concept behind the exposition architecture—a blend of Spanish-Colonial and Mission styles—in his introduction to Winslow’s The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition. Goodhue criticized the architecture of previous world’s fairs as following a style that failed to relate to anything in the exposition or to that which the event was commemorating. Since San Diego’s fair was more cultural and regional, he sought to reflect the area’s past and “to obtain, in so far as this was possible, something of the effect of the old Spanish and Mission days and thus to link the spirit of the old seekers of the fabled Eldorado (the mythical city of gold) with that of the twentieth century.”

The blending of the Spanish-Colonial and Mission styles is evident as you cross the bridge and approach the west gate. On the left just before the gate is the Administration Building and to the right of the gate is the Fine Arts Building (both now part of the Museum of Us, formerly the Museum of Man). These two buildings reflect the Mission influence while the California Building with its soaring tower and dome adheres to the decorative Spanish-Colonial style.

There’s disagreement over who actually designed the Administration Building. Balboa Park historian Richard Amero attributed the building to Irving Gill but, according to Gill biographer Bruce Kamerling, Gill left the project in 1912 to work on a series of designs for the model industrial town of Torrance, California. Winslow claims in The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition that he was the designer and that “its practical requirements” were executed by Frank Allen, Jr. Maybe the answer is in the design of the windows.

It’s interesting to note that decorative ornamentation was added around the entrance of the Administration Building in 1914 three years after it was built; perhaps to tie in better with the adjacent California Building. However, the ornamentation was removed in the 1950s.

Temporary versus permanent buildings

Goodhue considered most of the structures designed for the exposition to be temporary. Among the structures that were “intended to express and to ensure permanence” were the Cabrillo Bridge and the California Quadrangle that includes the California Building with its tower and dome and the Fine Arts Building. The buildings surrounding the Plaza de Panama, the large central “town square,” and those along El Prado, the east-west boulevard, were all, according to Goodhue, intended to be razed and replaced by a large formal garden. The Botanical Building, designed by Winslow, would have become a centerpiece of the new garden, along with the permanent open-air Organ Pavilion, given to the exposition and city of San Diego by brothers John D. and Adolph B. Spreckels.

However, the citizens of San Diego fell in love with Goodhue’s illusion of a “city-in-miniature wherein everything that met the eye and ear of the visitor were meant to recall to mind the glamour and mystery of the old Spanish days.” Over the years, some of the buildings were renovated to bring them up to permanent standing while others were completely replaced with new buildings, like the Timken Museum of Art that replaced the Home Economy Building. The Botanical Building is currently undergoing restoration to return it to its 1915 splendor and the Mingei International Museum, has been re-envisioned as a new structure within the shell of the historical House of Charm, formerly the Indian Arts Building.

California Quadrangle

Once through the deep archway of the west gate, the stage is set. The California State Building and the Fine Arts Building, as they were called at the time, are connected by arched arcades that enclose the Plaza de California and form the California Quadrangle. Designed by Goodhue and considered the focal point of the exposition, these permanent buildings reflect the highly ornate Spanish-Colonial Revival style complemented by the straightforward simplicity of the Mission style, an appropriate setting for an exposition in Southern California.

Clarence S. Stein, who worked in Goodhue’s office at the time, added that Moorish influence by way of Spain is also present. In his essay in The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition, Stein pointed to the contrast derived from “the great surfaces of blank wall with occasional spots of luxuriant ornament” like the California Building façade and “love of bright color shown in the use of polychrome tiles” like the blue, green, yellow, black, and white tiles on the dome.

To achieve a sense of harmony across the exposition and relate architecturally back to the iconic California Building, other buildings were dressed with smaller domes, turrets, and belfries; colorful decorative tiles; and clusters of elaborate ornamentation. Architect David Marshall described in San Diego’s Balboa Park how ornamentation was designed for the temporary buildings. First, sculptor H. L. Schmohl (based on drawings by Winslow) molded the decorative elements out of clay then created castings out of “staff plaster,” plaster of Paris reinforced with hemp fiber. Afterwards, the inexpensive and lightweight castings were nailed to wooden framing.

As you walk around the Central Mesa see if you can identify other buildings that date back to the 1915 Panama-California Exposition. Hint: some of them even have the date embedded in ornamentation above entry points to the arched arcades!

Frontispiece of the California Building

The ornate 72-foot tall frontispiece on the façade of the California Building blends characteristics of Plateresque, Baroque, Churrigueresque, and Rococo, according to park historian Richard Amero. The result is a unique hybrid design style that inspired Spanish-Colonial Revival architecture in California.

Stone ornamentation and relevant iconography surround the façade’s door and window while statues by Furio and Attilio Piccirilli pay homage to important figures in San Diego’s history. At the very top is the United States shield. Just below that is Father Junípero Serra who presided over California’s missions and founded the Mission San Diego de Alcalá in 1769. Below Serra are busts of Charles V and Philip III of Spain on the right and left respectively. Then come the coats of arms for Mexico on the right and the State of California on the left. Next on the right is Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo who sailed into San Diego Bay in 1542 and for whom the bridge and other landmarks are named. And opposite Cabrillo is Don Sebastián Vizcaíno, who named San Diego when he was mapping Alta California for Spain in 1602. The next pair of busts are Gaspar de Portolá on the right who was the first Spanish governor of Southern California. Opposite de Portola is George Vancouver, an English explorer who mapped the North American west coast from San Diego to Alaska between 1791–1795. Finally, Fray Antonio de la Ascensión, a Carmelite historian who wrote the account of Vizcaíno’s expedition, right, and Father Luís Jayme, a Spanish-born Franciscan missionary who was killed in a raid on the San Diego mission.

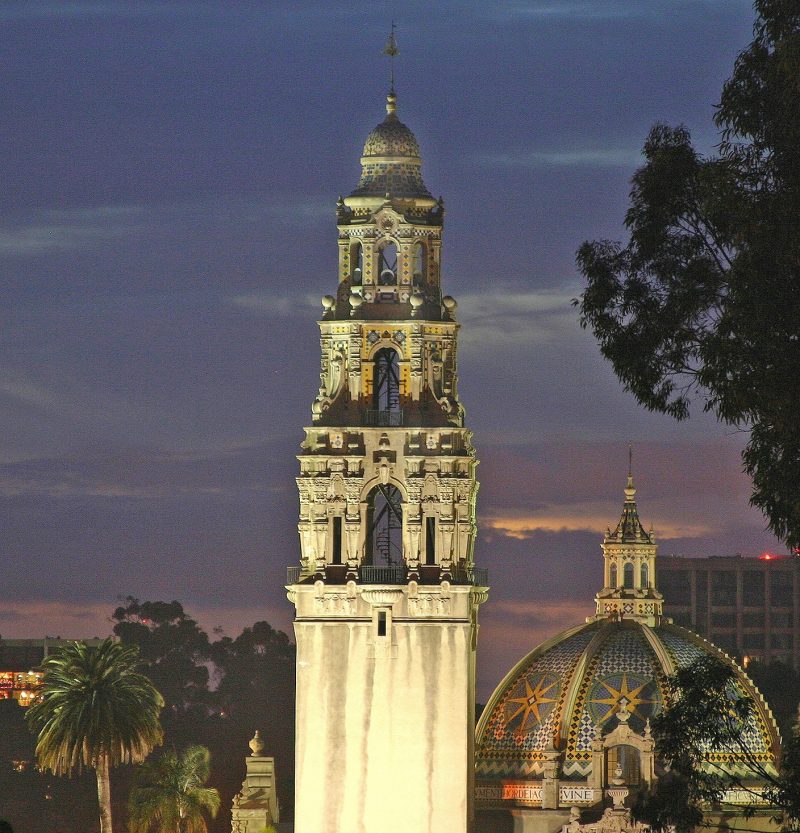

Tower

Designed by Goodhue, the tower rises 200 feet from the ground to the top of the wrought iron weathervane crafted into a Spanish ship. The tiered tower was influenced by Cordoba’s Mozarabe and Mudejar cathedral towers and Seville’s Giralda. The tall base of the tower is simple with no architectural embellishments except for a few small windows. The upper portion consists of three open belfries culminating in a bell-shaped colored tile dome. According to photographer Andrew Hudson the three tiers shape shift from a quadrangle to an octagon and then to a circle. The first belfry is heavily adorned with Churrigueresque ornamentation and no tile work. The other two belfries feature less Churrigueresque decoration and more geometric patterns of yellow and blue glazed ceramic tiles and beads like on the dome.

Dome

The large dome, designed by Goodhue, was modeled after the Santa Prisca dome in Taxco, Mexico, which also incorporates large starbursts in circles. (I referred to this earlier as a compass rose in relation to the lamp posts on the bridge.) A Latin inscription of Deuteronomy 8:8 from the Vulgate of St. Jerome runs around the tiled base of the dome. Translated into English, it reads, “A land of wheat, and barley, and vines, and fig-trees, and pomegranates; a land of olive oil, and honey.” In this context the verse is a metaphor for the importance of agriculture to Southern California and the opportunities for future prosperity with the opening of the Panama Canal.

Tiles

The tiles were created by Walter Nordhoff’s California China Products Company in National City, which produced over 10,000 highly decorative Hispano-Mooresque-style ceramic tiles for the buildings of the 1915 Exposition, including the California Building’s tower, main dome, and two smaller domes. The sixty-foot high central dome alone required hundreds of polychromatic glazed ceramic tiles, also called faience tiles.

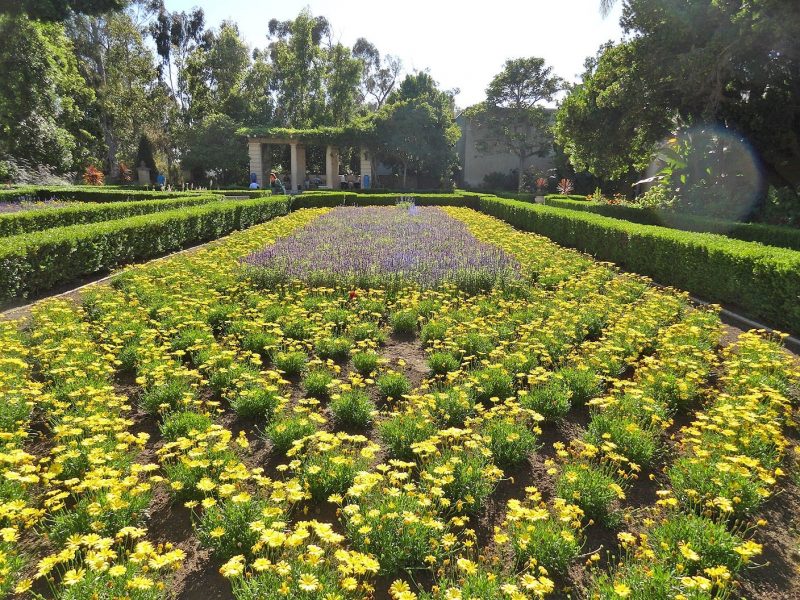

Alcazar Garden

Don’t miss this lovely formal garden behind the Mingei International Museum. During the 1915 Exposition it was called the Gardens of Montezuma. The name was changed in 1935 to Alcazar Garden when it was redesigned by architect Richard Requa in the manner of the gardens at Alcazar Castle in Spain. The Moorish-style geometric fountains decorated with multicolored tiles were added along with benches to accompany the existing pergola. Boxwood shrubs border the colorful landscaped beds that are constantly changing depending on the flowers in season. Together these design elements strike a peaceful and relaxing tone.

Palm Canyon

You can easily reach Palm Canyon from Alcazar Garden. Cross the small adjacent parking lot and head east towards the wooden bridge. The original rustic bridge built for the 1915 Exposition is long gone but there’s a new sturdy bridge with stairs that lead down to the canyon floor where you’ll find 450 palms representing 58 different species within a two-acre area. An original group of Mexican fan palms planted under the direction of Kate Sessions date back to 1912. You’ll also spot Moreton Bay fig trees that were planted in the 1930s.

The bridge and stairs were part of a 1975 master plan for Palm Canyon that was developed by KTUA Landscape Architecture in conjunction with the City of San Diego. The plan also included upgrades to the paths that take you to the archery range, the 1935 cactus garden in the Palisades, and to the International Houses and House of Pacific Relations, “pacific” in this case meaning “peaceful.”

Botanical Building

The idea for the Botanical Building came from Alfred D. Robinson, the world’s leading begonia breeder at the time. He thought it would be a good way to introduce rare tropical and sub-tropical plants during the 1915 Panama-California Exposition while highlighting San Diego’s amazing growing climate. Designed by Carleton Winslow of Bertram Goodhue’s office and engineered by Thomas P. Hunter, the Botanical Building is a narrow rectangular structure with a central dome and short barrel vaults on either side. Steel trusses support the vaults and 75,000 feet of bent redwood lath. The building measures 250 feet long, 75 feet wide, and 60 feet high. At the time, Esther Hansen, editor of the official 1915 Exposition guide book, described the Botanical Building as one of the largest lath-covered structures in existence. In The Architecture and the Gardens of the San Diego Exposition, Winslow described the “Lath House” as “an ornamental example of the lath-covered, open conservatory common to Southern California.”

In front of the Botanical Building are two reflecting pools divided by a balustraded walkway. The smaller squarish pool is closest to the building while the dramatic long pool extends all the way to El Prado, the avenue that runs east and west through the Central Mesa. Both pools are populated with water lilies and other aquatic plants. “The pool is invaluable for its reflections; the inverted pictures are broken by the water growth which increases in density as it approaches the upper front of the Botanical Building in almost swamp-like richness of vegetation,” wrote Winslow of “La Laguna.”

Restoring the Botanical Building

The Botanical Building was adopted by the Balboa Park Conservancy—a nonprofit that provides expertise, advocacy and resources to envision, enhance and sustain Balboa Park—as its first major restoration project in the park. Roesling, Nakamura and Tejada Architects (RNT) and Spurlock Landscape Architects in collaboration with horticultural designer Tres Fromme were chosen to undertake the restoration.

The goal is to return the Botanical Building to its original 1915 design and undo changes made over the years that altered its original appearance. For example, during a major renovation in 1957, arcades that flanked both sides of the entrance and spanned the barrel vaults were removed. A pergola that was a focal point in the open landscape was demolished and planting beds were removed. The historic arcades and pergola will be restored. In addition, facilities will be enhanced, such as water-efficient irrigation and energy-saving lighting, and new amenities added, including restrooms and educational opportunities.

I asked Kotaro Nakamura of RNT what it’s like to work on an historical renovation compared to designing a building from the ground up. “Architects are always bound by context. A new building has its site, weather, landscape, clients, budget, etc. The Botanical Building has its history as its context just as the Inamori Pavilion at the Japanese garden (also designed by Nakamura) has its own historical context in a different way. Our job is to interpret the meaning and come up with the best possible outcome within the context of time.”

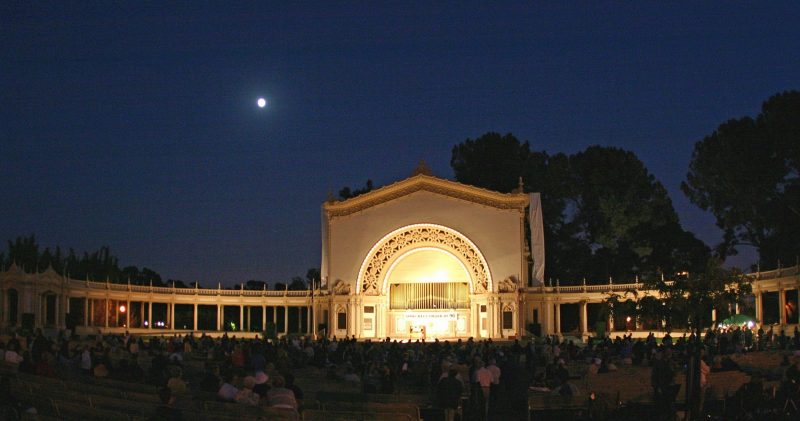

Spreckels Organ Pavilion

The organ and pavilion were a gift to the people of San Diego by John D. Spreckels and his brother Adolph B. Spreckels.

“In consideration of the good people of San Diego, of our desire to contribute something to their benefit and enjoyment, and of our earnest wish that they may live and prosper in peace and harmony….” reads the dedication plaque.

The Spreckels Organ Pavilion comprises a main building and a semi-circular colonnade with Corinthian-style columns, designed in the Italian-Renaissance style by architect Harrison Albright. The design was considered by some to be conventional compared to the more daring designs of Goodhue’s exposition buildings. The main building with the large arched opening houses the Opus 453 pipe organ built in 1914 by Austin Organ Company. The company website describes Opus 453 as a “four manual, 46 rank instrument that plays in the open air when in use.” The section that houses the organ was designed to face north in order to protect the large instrument from the sun while the semi-circular colonnade was designed to embrace the audience. To symbolize the musical function of the organ pavilion the heads of angels blowing trumpets and Pan playing pipes can be spotted amongst the lavish decoration.

The Spreckels Organ Pavilion has stood the test of time with the help of a number of renovations, including restoration and upgrading of the electrical system and exterior lighting in 2006.

Architecture between the expositions

Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego (San Diego Museum of Art), 1925/1966

Original building, 1925

The Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego opened to the public in February 1926, replacing the Sacramento Valley Building that Goodhue and Winslow designed for the 1915 Exposition at the head of the Plaza de Panama. An inscription on the building acknowledges both William Templeton Johnson and Robert W. Snyder as the architects. In 1978, the Fine Arts Gallery was renamed the San Diego Museum of Art in recognition of the collection’s inclusion of applied and decorative arts.

Like the 1915 California Building, the museum features a richly embellished entryway, which was inspired by the plateresque façade of the University of Salamanca. The façade is symmetrical with the entrance in the center and five windows on either side within the lower portion of a massive plain flat wall. The Renaissance-inspired motifs in the facade’s décor are finer than those on the California Building. Besides the motifs in the elaborate frontispiece, note the decorative elements in the ornamental framing of the ten windows. Look closely and you’ll see vignettes of artists at work featured in the arched pediments above each window.

Architectural sculptor Chris Mueller, who supervised architectural details of the 1915 Exposition buildings, and his son added sculptural elements to the museum frontispiece. The Muellers sculpted the life-sized statues of the Baroque Spanish painters Diego Velázquez, Bartolomé Murillo, and Francisco de Zurbarán as well as the coats-of-arms of Spain, the United States, California, and San Diego. In a 1982 essay, Martin E. Pedersen, then the Museum’s curator of paintings, wrote that the Spanish painters, including José de Ribera and El Greco, “coexist in absolute harmony with the Italian Renaissance sculptors, Donatello and Michelangelo, represented by replicas of St. George and David respectively.” Mueller’s personal connection to the 1915 buildings may be why this building also coexists in harmony with its earlier counterparts.

Johnson incorporated sea shells in a number of his buildings, a reference to Saint James. Here, a very large shell is prominently placed in the arched pediment above the museum’s entry and smaller replicas form a decorative border that wraps around the top of the building like a frieze. Legend has it, according to Pedersen, that “Saint James was transported to the coast of Spain on a shell, as the early Spaniards were carried to the New World in galleons. The shell has traditionally become the symbol of the saint in the arts.” In this case, San Diego. “It is the extravagantly covered entrance…that suggests the treasures within. The building is a worthy repository for the wealth it contains.”

It’s interesting that the entrance to the 1915 California Building as well as to the 1925 Fine Arts Gallery have arched pediments above their doors, likely a reflection of the Mission influence, and both incorporate sea shell motifs. The eleven shells outlining the arched pediment on the California Building are easy to miss. Go back and look if you missed them!

West wing expansion, 1966

In 1966, the Museum’s west wing expansion was completed and includes the May S. Marcy Sculpture Court and Garden. As part of the “Art of the Open Air” sculpture walk, you’ll find works by significant artists in the court and garden, as well as in front of the museum. Remember sculpture is designed to be viewed from 360 degrees so walk around and observe the sculptures from all sides and pay attention to how they’re positioned within the environment. And be sure to look at the Malcolm Leland gates that I told you about when I introduced you to Panama 66. Oh, and I discovered four more Leland gates in the back of the museum that are worth a look-see!

Another interesting point about the museum is its physical relationship to other structures in the park. Stand in the center of the front door and face south. The center of the museum lines up with the center of the Organ Pavilion and that sightline cuts straight through the center of the statue of El Cid Campeador by Anna Hyatt Huntington. Isn’t that cool?

Museum of Natural History, 1933/2001

Original building, 1933

The San Diego Natural History Museum, dedicated on January 14, 1933, was designed by William Templeton Johnson who is best known for his Spanish-Revival architecture. Johnson’s interest in Spanish architecture solidified with the popularity of the Panama-California Exposition, according to Sarah J. Schaffer in “A Civic Architect for San Diego.” Schaffer also points out Moorish influences in Johnson’s design of the museum façade, such as the succession of ten arches on either side of the entry and a decorative geometric pattern of yellow and blue tiles under each window. These colors relate back to the dome on the California Building and provide a sense of continuity.

Rather than applying a red-tile roof, like he did on the San Diego Museum of Art, which is more in keeping with his other Spanish-Revival buildings, Johnson incorporated a decorative screen and balustrade on the flat roof. The symmetrical balustrade is composed of 20 segments with 10 on each side of the entryway. The segments harbor two seahorse-like creatures that flank a circular shape with an open center. Geometry is definitely at work in the alignment of the ten balustrade units in relation to the ten arched windows and four rather plain inset windows below.

Like the Museum of Art, the entry advances from the building. It’s a welcoming gesture and makes the entry feel more significant. Two flights of 10 steps with a landing in between take you to the arched doorway flanked by columns that are highly ornamented on the lower half and fluted on the upper half. The columns are capped with a decorative Corinthian-style capital. There are no sculptures of people in this facade, only a menagerie of animals, leaves, and shells.

The heads of longhorn sheep punctuate both sides of the door’s arch. Look closely and you’ll find that their heads accompanied by two smaller critters, a mouse and a squirrel, I think. The portico above the arch and between the two columns appears to contain long-necked fowl. Above the columns are bison heads. Higher up overlooking the park are two elongated Egyptian-style cat-like creatures and at the very top perched on the pediment is a large two-headed winged creature, maybe an eagle. While the subject matter is befitting an institution dedicated to natural history, Martin E. Petersen found the decorative scheme around the doorway to be “one of incongruous complexity” that is aesthetically “chaotic rather than harmonious.” (“William Templeton Johnson: San Diego Architect, 1877–1957”) This mashup was likely due to the fact that Johnson was asked to use existing stock, or ready-made, sculptures that he had to collage together.

Natural History Museum expansion, 2001

What you see today is a two-faced building, literally. The entrance was relocated to the opposite side of the building as part of the 2001 expansion designed by Richard Bundy and David Thompson Architects. While the expansion more than doubled the size of the museum, the entrance departed from the Spanish-Revival style of architecture by adding a four-story glass atrium with stairs leading down to a pop-out entryway designed in the vein of postmodernism, an approach that blends elements of historical and modern styles. Much to the chagrin of some. San Diego Union-Tribune arts and entertainment writer Welton Jones said in a May 31, 1998, article, “What’s wrong with this picture is that filmy, soaring glass, which is grimly at odds with the Spanish-Colonial architecture everywhere else along the Prado.” In a June 7, 1998, letter to the U-T, historian Richard Amero responded in support of Jones’ story and further criticized the Natural History Museum for deviating from the Spanish-Colonial architectural style and questioned the review process. “Citizens and visitors will be faced with the question how this out-of-place, out-of-character, out-of-history intrusion could have occurred.” He also criticized earlier deviants including the Timken Museum (1965), San Diego Museum of Art’s west wing (1966), and the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater (1972).

This seems like a good point to recall that the original 1910 park master plan by Samuel Parsons cautioned against sculpture and buildings in the park. The Olmsted Brothers resigned from the 1915 Exposition project when the location was moved to the Central Mesa because they felt it was at odds with Parsons’ rural park plan. And most of the 1915 structures designed by Bertram Goodhue and Carleton Winslow were intended to be torn down after the exposition closed and thus were not built with durable materials or in a manner expected to last. They were to be replaced by a large formal garden and lots of open park space. But a group of citizens sought to retain the exhibit buildings. In 1922 and 1933, workers supported by Federal relief programs helped shore up the temporary buildings. Some have even been completely rebuilt and restored. The buildings became homes to museums and other cultural institutions that San Diego has grown to love and rely on.

Since there’s no turning back and buildings in the park are here to stay, should new structures be required to follow the architectural style set forth in 1915?

Type on buildings

An alternate approach to signage is evident on the Natural History Museum, as well as other “newer” buildings. The institution names are mounted in large type on the buildings themselves. The Natural History Museum’s new addition, for example, has the museum name on both ends of the north side in Times New Roman, an old style serif typeface by Stanley Morison released in 1932. In contrast, “Museum Entrance” positioned above the new entry is set in Futura, a geometric sans-serif typeface by Paul Renner released in 1927. The typeface on the more traditional parts of the north side is a classical style while the postmodern portion of the façade incorporates a more modern typeface designed in the spirit of the Bauhaus. Was this by design? Are these at odds with each other or do they aptly represent the contrasting architectural styles?

Moreton Bay Fig

On the north side of the Natural History Museum meet a very old Moreton Bay Fig tree that’s almost as old as the park itself. Put in place for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, the then small young tree was the center piece in a formal garden. Now its branches almost fill the same space. Measuring 75-feet tall this magnificent specimen is among the largest of its kind in California. To protect the tree’s sprawling roots the area has been fenced off for a long time. Plans are currently underway for a viewing platform designed by landscape architect Patrick Caughey of Wimmer Yamada & Caughey, a project sponsored by Friends of Balboa Park, which will allow visitors to get up close and marvel at the 123-foot reach of the tree’s canopy and its 486-inch waistline without harming one of the park’s oldest arboreal residents.

1935 Exposition Architecture

Requa’s plan

When Goodhue was put in charge of architecture for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition he was working with a clean slate, a white page, a blank canvas. When Richard Requa was put in charge of architecture for the 1935 California-Pacific Exposition twenty years later the context was very different. Not only did he have Goodhue and Winslow’s buildings and the existing overall park layout to take into consideration, he also had the Organ Pavilion, and Johnson’s two new museum buildings.

These existing structures became the nucleus for the second exposition with additional buildings designed by the exposition architectural team led by Requa and including Louis Bodmer from Requa’s office. With the exception of the Ford Building, which was designed by industrial designer, graphic designer, and architect Walter Dorwin Teague. The decoration on the new buildings was assigned to Hollywood artist Juan Larrinaga, which says something about the expectations of the planners and promoters. Was it just a Hollywood set? Most of the decoration was temporary and has been dismantled leaving behind large empty dull walls and buildings that look abandoned.

At least Johnson’s buildings adhered to some degree to the Spanish-Revival architectural vocabulary. Requa’s did not, although, his inspiration came in part from an existing 1915 Exposition structure—the New Mexico Building (in 1935 Palace of Education, now the Balboa Park Club), the only surviving building from the first exposition in the Palisades, the southern end of the Central Mesa. The building’s earth tones, rounded contours, flat roof, and rough-hewn vigas that projected from the walls guided the design of the adjacent building currently called the Recital Hall.

To better understand Requa’s intentions, park historian Richard Amero explains that Requa conceived an architectural plan for the Palisades that showed “how the forms of indigenous architecture in the American southwest and in Mexico could be used to produce a distinctive American style of architecture.” Teague’s design was not consistent with Requa’s plan but “Requa chose to regard it as the peak of an evolutionary progression in building from the pre-Columbian past to the enterprising 1930s, an era when many American architects were trying to divest themselves of European Gothic and Neo-Classical influences.”

Ford Building

The Henry Ford Museum describes the two circular forms that comprise the Ford Building as “resembling two engaged gears.” San Diego designer Calvin Woo, in collaboration with exhibition designer Roger Tierney, researched the building while preparing a proposal for the Air and Space Museum, which occupied the Ford Building. He describes the two circular shapes as interpretations of a car’s carburetor and manifold. Seen from above the two circles form a figure 8 to symbolize the Flathead V-8 engine produced by Ford Motor Company at the time (1932–1953). The small circular building with the vertical ribs that light up at night, is the point of entry. Once inside the small rotunda visitors were directed to the larger circular exhibition space. The circular gallery design allowed for an efficient flow of tourist traffic in and out of the building. In the center of the larger circle is an open-air courtyard with a fountain composed of a triangle, a small circle, and a larger circle that together form the V-8 logo. The symbolism throughout the Ford Building paired with practicality represented a shift away from historicism, in which designers were beholden to follow historical styles, towards the modernist problem-solving principle “form follows function.”

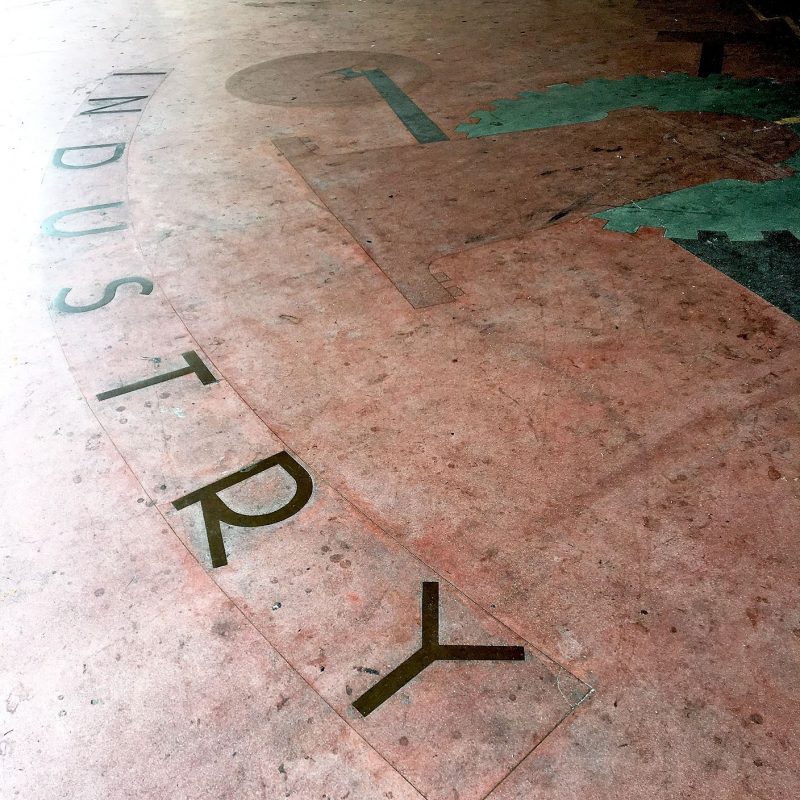

A graphic design highlight in the Palisades

Find your way to 1935 Palace of Electricity and Varied Industries Building, known now as the Municipal Gym. It’s one of the bare-bones buildings that was stripped of its decoration. The word “Gymnasium” is below the identification number 2111, spelled out in a poorly-spaced sans serif typeface all caps with a quirky uppercase G. Go to the entrance and look down on the floor outside the doors where you’ll find wonderful inlay artistry. Stylized graphic symbols of lightning bolts and gears symbolize electricity and industry. Nearest to the doors, the word electricity is spelled out in custom geometric sans-serif all caps letters on a horizontal baseline. Below the graphic illustration the word industry is spelled out in the same letter style but on a curved baseline. The artwork is inlaid in what appears to be colored concrete. I’m still trying to find out more about this beautiful work. While it pains me to see it unprotected and neglected, it appears to have weathered the years well.

1965 Timken Museum of Art

When the architect John Mock designed the Timken Museum for Frank L. Hope and Associates, he ignored the park’s existing architectural styles and broke with historicism to achieve “one of the most outstanding, public, examples of post-War modernist architecture in the region,” according to Keith York in “Modernism on Display: The Timken Museum of Art” at Modern San Diego.

Mock’s design dissolves the boundaries between the inside of the museum and the beautiful park environment beyond its walls. In order to bring the park into the museum Mock incorporated floor-to-ceiling windows at certain points on each of the four sides of the long lobby of the H-shaped building. The entrance, which faces the Plaza de Panama to the west, features a glass entryway that’s a little less than one third of the width of the façade. Another storefront glass entrance at the opposite end of the lobby faces east and overlooks the long reflecting pool. On the north and south sides of the lobby, courtyards with uniquely designed gardens fill in the open spaces of the H layout. Tall glass windows let light into the museum while providing views into these intimate spaces and glimpses of the park on the other side of a decorative gate.

Lighting designer Richard Kelly created another way to let the outside in. Kelly designed the exterior and interior lighting, including a unique skylight scheme that serves up filtered sunlight and responds to the sun’s path across the sky.

Lead designer Howard Shaw designed the frieze above the entrance, a pattern of square bronze bas-reliefs with a floral motif that appears to be based on the museum’s graphic symbol. Shaw was also responsible for the gates, railings, and grill work around the exterior. The pattern of the gates and railings is also based on the museum’s symbol but with much less detail than in the frieze. Look closely and you’ll see it when the positive and negative interplay settles down! The open wrought iron tooling and the light airy feeling soften the rectilinearity of the white travertine façade and visually connects with the intricate designs on nearby buildings, like the Leland gates across the plaza and the metal grill work surrounding the Museum of Art entrance.

The stylized graphic symbol looks to be based on plant forms. The X-configuration of four leaf-like elements with smaller organic elements in between could also symbolize Mock’s concept of breaking through the walls to create a synergistic relationship with the park. At any rate, it’s tastefully executed and the applications to the frieze, gates, and railings harmonize well with the architecture.

Optima is a good choice for the logotype. Designed by German type designer Herman Zapf in 1958, Optima is classified as a humanist sans serif, a term that refers to typefaces whose structure leans more organic than mechanical and reveals some evidence of the human hand. Zapf, who was inspired by the traditional Roman monumental capitals found on the Trajan column, applied similar proportions to Optima’s capitals. The letterform strokes have a subtle taper and the terminals are slightly concave. Optima is an elegant typeface that pairs well with this exemplar of modernism; although, the placement of the symbol and logotype on the building could be more suitably integrated into the architecture. Or removed altogether.

2015 Inamori Pavilion in the Japanese Friendship Garden

When the 1915 Panama-California Exposition ended, the traditional Japanese tea pavilion and garden that had been exhibited just north of the Botanical Building continued to be operated by the Asakawa family until it was dismantled in 1941. In 1955, discussions got underway for a larger Japanese garden in Balboa Park. Members of the Yokohama Sister City Society worked with the City of San Diego to identify an 11-acre site near the Organ Pavilion. The architectural firm Fong & LaRocca Associates and Takeo Uesugi, landscape architect and Japanese garden design consultant, were chosen to design a master plan for the site. In 1985, landscape architect Takeshi Ken Nakajima named the garden San-Kei-En, “garden of three types of scenery—pastoral, mountain, and lake.” The first phase opened in 1990. The second phase, completed in 1999, added the tea pavilion, garden study center, koi pond, and bonsai garden. In 2015, when the third phase was completed a grove of 200 cherry trees had been added, as well as an azalea and camellia garden, a water feature, and the elegant Inamori Pavilion, the first building in Balboa Park to be LEED certified. The architect, Kotaro Nakamura, shares his design vision in this video of the Inamori Pavilion by Bread Truck Films.

2021 Comic-Con Museum

Three names in different typefaces, none of which are included in the signage guidelines, adorn the building on the corner of Presidents Way and Pan American Plaza in Balboa Park’s Palisades area. It was named the Federal Building when it was constructed for the 1935 California-Pacific Exposition. Later, the San Diego Hall of Champions Sports Museum moved in until it closed in 2017. Now, a banner that hangs out front reads “Comic-Con Museum Future Home.” While Adam Smith, the museum’s new director, isn’t sure it’ll be called a museum he shares a lot of interesting ideas of what it might become in this Voice of San Diego article. In the meantime tune in to Comic-Con@Home for activities, games, and updates.

2021 Mingei International Museum

The word mingei was coined by Japanese philosopher Sōetsu Yanagi and means “art of the people.” Inspired by Yanagi, Martha Longenecker, a ceramics professor at San Diego State University, founded the Mingei Museum in San Diego. The original museum, located at University Town Center, opened in May 1978 and in August 1996, the museum relocated to a 41,000-square-foot facility in Balboa Park’s House of Charm on the southwest corner of the Plaza de Panama. The museum is currently undergoing a massive renovation and expansion and is scheduled to reopen in 2021.

The new plaza level will be open to the public and accessible through six points of entry, one of which is the Alcazar Garden. Visitors will have free access on this level to a gallery, store, restaurant, and center for learning. The second level will include galleries where exhibitions will present works of folk art, craft, and design that further the understanding of art of the people (mingei) from all eras and cultures. This level will also incorporate an art reference and media library that showcases the museum’s collection. Outdoor terraces overlooking the Plaza de Panama that have been sealed off for decades will be reopened. Plans also include opening the building’s historic bell tower.

Architect Jennifer Luce of LUCE et Studio designed the transformation of the Mingei International Museum. Together with Rob Sidner, Mingei’s executive director, Luce will present a virtual tour of the new space during San Diego Design Week.

Have a great question? Submit questions directly to SDDW presenters here!

About Susan Merritt

Susan Merritt researches and writes about visual communication, material culture, and design history. She completed postgraduate study in graphic design at the Basel School of Design and earned an MA in Design Research, Writing and Criticism from the School of Visual Arts. She is Professor Emerita of SDSU's School of Art + Design where she taught graphic design and graphic design history while maintaining a professional practice. Merritt is a founding member of AIGA San Diego and contributing writer to AIGA’s Eye on Design blog. She and husband Calvin Woo co-founded Design Innovation Institute, which fosters traditional and non-traditional areas of design and supports student scholarships. She sits on San Diego Design Week’s advisory board and is an active member of the steering committee.