Explore the Tour

Explore a new side to San Diego’s beloved Balboa Park with a self guided tour of the park. This outdoor excursion will help discover some of the park’s tightly-packed history and highlight its landscape design and architecture. The tour also celebrates the designers and other significant people who have contributed to the park’s design history. Due to the size of Balboa Park, this tour will be split into three segments based on the park’s geographic areas — West Mesa, Central Mesa, and East Mesa. Enjoy these self-guided tours one at a time or combine all three into a single trip. Participants are encouraged to bring a picnic and bask in the beauty of one of the most unique public urban parks in the country.

Also visit:

Public Spaces by Design: Balboa Park East

Public Spaces by Design: Balboa Park Central

Photos by Calvin Woo and Susan Merritt

____________________________________________

West Mesa, the park’s front yard

The West Mesa runs along Sixth Avenue in Bankers Hill from Elm Street to Upas Street, includes the west slope of Cabrillo Canyon leading down to US Route 163, and encompasses the 15-acre Marston Hills estate on Seventh Avenue. The West Mesa is surrounded by downtown to the south, Hillcrest to the north, and Bankers Hill to the west, where you’ll still find remnants of a historic neighborhood in spite of encroaching condominium high rises. The West Mesa is very walkable with lots of green open space and inviting spots to picnic. We’ll start from the northwesternmost corner and work our way south.

Bring a picnic

Pack lunch or order takeout from a nearby restaurant and enjoy a picnic while basking in the beauty of one of the country’s most unique public urban parks. One of my favorite nearby places is Bread & Cie in neighboring Hillcrest. They offer a selection of specialty sandwiches on their delicious freshly-baked European-style artisan breads.

Save room for dessert!

After your park excursion, stop by either the Bankers Hill or Little Italy location of Extraordinary Desserts, which, believe me, lives up to its name. On Thursday, September 10, and Friday, September 11, mention San Diego Design Week (SDDW) and get 20% off one of the featured Pavlova desserts, a crisp baked meringue filled with Devonshire cream and fresh berries. Both locations were designed by the extraordinary architect Jennifer Luce of Luce Et Studio who will discuss her collaboration with owner and extraordinary pastry chef Karen Krasne in “The Architecture of the Pavlova” during SDDW.

Start at the Sixth & Upas Gateway sign

Let’s begin on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Upas Street at the Balboa Park Trails gateway sign. You’ll find a sign like this one at the park’s four other main entry points: Morley Field and Golden Hill in the East Mesa, Park Boulevard in the Central Mesa, and Marston Point at the southernmost tip of the West Mesa. The gateway signs are part of a comprehensive sign system developed by Stuart White Design and adopted by the City of San Diego in 1992. RSM Design of San Clemente has been working over the past couple of years in collaboration with the Balboa Park Conservancy on an update to this system, but to the best of my knowledge at the time of this writing none of the new signs has been installed.

Map of the West Mesa

Have a look at the map and get acquainted with the lay of the land. The map on the gateway sign was developed in 2009 by KTUA, a San Diego landscape architecture firm. The planners at KTUA mapped the park’s existing hiking, walking, and biking trails and analyzed points of interest using computer-based geographic information system (GIS) software. The main goal of the project was to identify options for discovering lesser known areas of Balboa Park while also providing direct walking routes to major destinations.

Balboa Drive and three paved sidewalks run north and south through the West Mesa and unpaved nature trails wind through Cabrillo Canyon. Loop trails that originate at each of the five gateways are color-coded and you’ll find color-coded information markers posted at key points along each route. The trails range in length from less than half a mile to more than seven miles and are labeled easy, moderate, and difficult accordingly.

Kate Sessions, Mother of Balboa Park

Before heading south to explore the West Mesa, let’s first ferret out some of the oldest trees in this area planted by pioneer horticulturist Kate Sessions whose commitment to the park earned her the moniker “Mother of Balboa Park.” Afterwards we’ll walk over to the Marston House and check out the gardens before heading south to Sefton Plaza.

Since the 1868 founding of City Park, as it was originally called, grassroots efforts were underway to plant trees and shrubs in what was a dusty, rocky tract of arid land. In 1892, Sessions led a more organized effort to develop the park when she was granted 30-some acres to set up a 10-acre nursery and garden right where we’re standing. As the designated city gardener, Sessions experimented with a variety of species to see which ones would grow in the San Diego soil and survive in the Southern California climate. In exchange for the allotted acreage, she was required to plant 100 trees on park land as well as provide an additional 300 trees and plants for other parks and streets throughout the city. Among the trees Sessions experimented with, according to cultural landscape specialist Vonn-Marie May, were Monterey cypress, Torrey pine, Cork oak, Acacia, Mission pepper, an assortment of Eucalyptus, and various exotic palms.

“Kate knew that she could grow plants. She also knew she could not design parks,” said Balboa Park historian Richard Amero. So Sessions sought advice from Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., the country’s foremost landscape designer. His advice to her was to confine what she planted to plants that grow on the shores of the Pacific and avoid trying to make San Diego’s park look like a park you’d find back east. While Sessions may not have followed his advice word for word, she did prove that her favorite palm, the Queen palm, grows very well on these shores.

Grid of Queen palms

Sessions was responsible for the Queen palms planted along Sixth Avenue, eight pairs per block from Elm to Upas with an additional pair positioned in the center of each oncoming street. Walk one block south and sight how the palms align with the middle of Thorn Street. As drivers approach, they’re greeted by a Queen palm that signals the western edge of the park. What an interesting way to visually connect the neighborhood with the park. This undertaking alone required over 500 trees! Some trees are now missing from the gridded layout, probably having succumbed to drought or disease over the years. Others, especially on the west side of Sixth were lost to development. Here and there, though, such as the block between Maple and Nutmeg on the east side of Sixth, you can still find her original plan intact.

Picturesque landscaping style

The Queen palm planting scheme is symmetrical, mathematical, and more ceremonious than the rest of the West Mesa, which in looking around appears “natural.” But the park’s natural state was a dusty barren tract of land covered with chaparral and, if winters were wet, blanketed with colorful indigenous wild flowers. We’re standing in the midst of a designed landscape made to appear natural according to the “picturesque” style of landscape design. This approach was introduced to the United States by Calvert Vaux, the British-American architect and landscape designer who, together with his junior partner Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., designed New York’s Central Park, one of America’s most famous picturesque-style parks. It was Vaux’s one-time partner, Samuel Parsons Jr., who in 1902 was commissioned to design the first master plan for San Diego’s then 1400-acre public space known as City Park.

George Marston, Father of Balboa Park

George Marston, who along with Sessions was a member of San Diego’s Park Improvement Committee, generously offered to cover the cost up to $5000 to hire Parsons, who had been recommended by Mary B. Coulston, former editor of Garden and Forest and the committee’s formidable secretary and publicist.

Marston, fondly referred to as the “Father of Balboa Park,” was the owner of Marston’s department store, a preservationist, and philanthropist. He was among the civic leaders who persevered for years to realize the potential they had long envisioned for the rugged canyons and dusty mesas that had been set aside in 1868 as City Park. That vision was further amplified when in 1987 the 4.5-acre estate of George and Anna Marston was gifted to the city for Balboa Park, assuring Marston, the architects, and landscape designers a place in San Diego’s design history.

Marston House

The 8,500 square-foot house, located on the 3500-block of jacaranda-lined Seventh Avenue was designed by local architects William S. Hebbard and Irving J. Gill in 1905. Influenced by English Arts and Crafts architecture popular at the time, the L-shaped house features a combination of building materials: exposed brick on the exterior walls of the first floor and four brick chimneys, tinted stucco on the second floor, and wooden shingles on the third floor, or attic. The south terrace overlooking the sloping lawn, the northside sleeping porch, and the balcony above the porte cochère reinforce the indoor-outdoor connection to nature, which was a hallmark of the Arts and Crafts movement. While a large house, the overall character is warm and inviting with its pitched roof, wide overhanging eaves, exposed rafters, and casement windows, which open outward to welcome in the out of doors.

Marston House gardens

The Marston grounds were originally designed by George Cooke who worked with Parsons. In keeping with the picturesque style planned for the adjacent park, grassy lawns stretch around the east, south, and west sides of the house and slope down towards the woodsy canyon. The trees at the Marston House are among the oldest in the park and were surely supplied by Sessions. A group of colossal centenarian Canary Island pines stands at attention at the head of the circular driveway while a robust California oak hovers above the porte cochère and sprawling white branches of towering eucalyptus trees extend outward as if safeguarding the estate. When Cooke was killed in an accident, Marston and his wife, with the help of Sessions, completed the design and plant selection. A vegetable garden with citrus trees, garden of flowers for bouquets, and a rose arbor were added to the north side along with a tool shed and hot house.

In 1926, the Marston grounds were updated with focus on the formal garden to the north, which is pretty much the design that you see today. Early sketches were done by John Nolen, the Cambridge, Massachusetts, urban planner who Marston commissioned to do the 1908 urban plan for the city. When Nolen was brought back to undertake another study of the city, Marston recruited him to work on his home. Nolen’s associate, Hale J. Walker, was eventually put in charge and worked closely with Marston’s eldest daughter, Mary, on what would become a two-year project.

Architectural features include a wall fountain with a small lead dolphin flanked by potted geraniums, a symbol of Marston that grew out of the slogan “smokestacks vs. geraniums” when he was compared to a pro-growth opponent during his unsuccessful mayoral campaigns. A teahouse overlooking a rectangular open lawn showcases decorative wall tiles which have been composed into still lifes. Don’t miss the capitals at the top of the teahouse’s wooden columns designed by architect William Templeton Johnson. They feature stylized sickle-shaped leaves and pods of the Blue Gum eucalyptus. Design in the details! You’ll also find the leaves and pods carved into the small corbels above the fountain near the cozy pergola that overlooks the canyon. In addition to the marvelous trees, the garden displays an array of shrubs, vines, and colorful seasonal flowers, including roses.

The Marston House and Gardens is managed by Save Our Heritage Organization (SOHO), which offers guided tours of the garden and interior of the house.

Architecture across the street from the Marston House

I’d be remiss if I didn’t call your attention to the other gems of early 20th century architecture on Seventh Avenue. While the private homes across the street are outside the bounds of Balboa Park, they’re significant to the architectural history of San Diego. Some of these homes were designed by Hebbard and Gill around the same time they designed the Marston house but they represent a shift away from the Arts and Crafts influence toward the emerging Prairie style championed by Frank Lloyd Wright, who had worked with Louis Sullivan of Adler & Sullivan in Chicago at the same time as Gill. Gill’s evolving design aesthetic was also influenced by the simplicity of indigenous architecture that he experienced while working with Marston on restoring California’s missions.

Compare the complexity of form, diversity of material, and the detailing on the Marston house with the houses across the street, particularly the newly restored 1905 home designed by Gill for Alice Lee and Katherine Teats at 3574 Seventh Avenue. The two houses on either side of 3574 were originally designed as companion rentals with all three buildings sharing the garden, which was landscaped by Sessions. Notice the straight lines, clean stuccoed walls, flatter rooflines, and arched doorways and entry points. Embellishment is kept to a minimum, in some cases nothing more than exposed timbers.

The work of local architects Frank Mead and Richard Requa is also represented on Seventh Avenue. You’ll hear more about them on the Central Mesa tour.

Next stop, Sefton Plaza

Sefton Plaza is located at the intersection of Balboa Drive and El Prado about halfway down the West Mesa. Let’s take a walk.

Integral color in concrete

I suggest following the Seventh Avenue sidewalk, the one tinted pink. According to Bruce Kamerling, San Diego Historical Society curator of collections, “This color had been recommended by Kate Sessions, San Diego’s famous horticulturist, who did not like the glare of concrete.” The pink-way follows the canyon contours so you’ll have picturesque views down into the canyon, beyond the canyon to the Central Mesa, and across the West Mesa towards Sixth Avenue. As you walk, notice the different types of evergreen, subtropical, and deciduous trees, their unique shapes, textures, and colors, and how they’re often clustered into natural-looking unstructured groves. The tallest, the eucalyptus, were intentionally planted for their height while the broadest, like the Moreton Bay Fig, have grown into amazing shade trees. These are among the park’s oldest generation of trees. You’ll also see a lot of young trees recently planted by San Diego Parks and Recreation as part of Tree Balboa Park, a reforestation project to plant more than 500 trees and help restore the park’s depleted tree canopy.

Design archaeological site

This route passes what I call a design archeological site. Tarnished swings and jungle gyms, and a peculiarly-shaped faded climbing structure with holes for foot perches or maybe for peeping through are all positioned in sandboxes to provide soft landings. These lingering pieces of playground equipment from 1968 intermingle with the dynamic new 2012 Evos play system with its twenty-first-century interactive learning components, colors, materials, and landing surfaces. Designed by Landscape Structures of Delano, Minnesota, this was a project of Friends of Balboa Park, a nonprofit with a mission “to preserve Balboa Park’s legacy for future generations through park-wide projects.”

Trees for Health Garden

Continuing on, we make our way through the illuminating Trees for Health Garden with its collection of plants selected for their healing properties, among them the South African sausage tree, New Zealand tea tree, Oregon grape, pomegranate, and cinnamon. This open-air classroom includes a gathering of square concrete stools designed by Steven Florman where visitors can sit and talk about the purposeful trees and their benefits. The concrete was poured in place and while still wet actual leaves were embedded into the top of each seat. The leaves eventually disintegrated leaving a fossilized record of what was growing at the time. Florman also created the informational signs strategically placed throughout the garden and built the stands they’re mounted on. The Trees for Health Garden is managed by volunteers in the spirit of the early days when ordinary citizens took it upon themselves to plant trees and shrubs in City Park.

Other sites along the way

Next, we’ll pass by the Cyprus Grove picnic area and alongside Redwood Circle where the Redwoods, native to Northern California, succumbed to drought and are being replaced with Torrey pines that better tolerate the San Diego climate. Just beyond Redwood Circle at the dirt trailhead is a dense patch of Mexican fan palms that park ranger Kim Duclo told me were planted by Sessions. Walk down the trail just a bit to get a real sense of the number and sizes of these trees.

Arrived at Sefton Plaza

When you pass the lawn bowling greens turn right towards Sefton Plaza located at the intersection of Balboa Drive and El Prado. Sefton Plaza, a gift to the city from Tom Sefton, San Diego banker, benefactor, and collector, was designed in 1989 by Pat Caughey of the landscape architectural firm Wimmer Yamada & Associates. “Every landscape ends up being a story,” said Caughey who’s now a principal at Wimmer Yamada and Caughey (WYAC). His design strategy is to understand a landscape’s original story so that what he designs fits. Since Sefton Plaza stands in the midst of an historical park, Caughey took a traditional, formal approach to ensure that hardscape, landscape, paving, and lighting would be compatible with the surroundings.

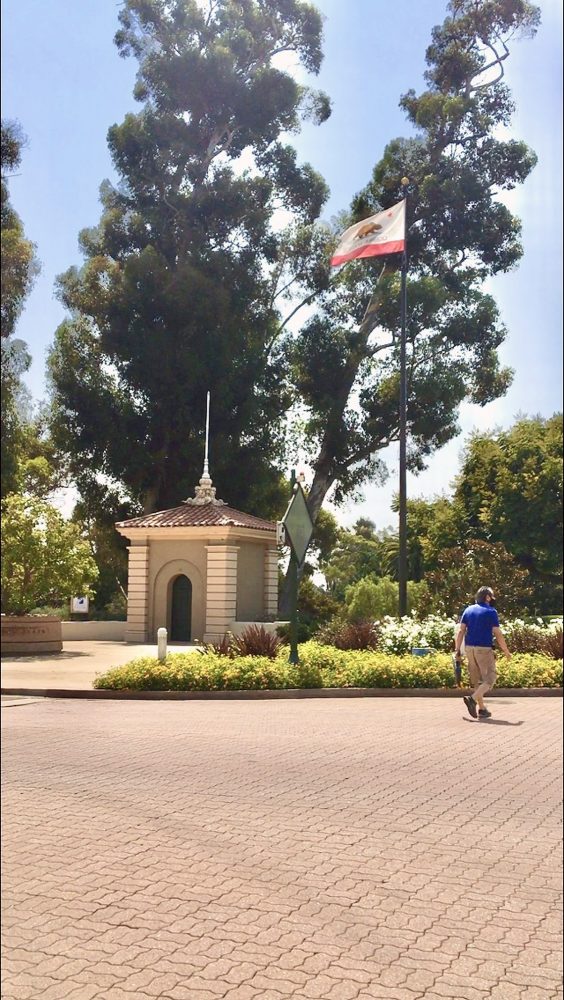

Fluted vertical light fixtures echo nearby historical lamp posts and outline the plaza’s four landscaped corners. Flags of the United States, California, San Diego, and Balboa Park fly high above the plots whose curved edges create a soft appeal. Pink interlocking pavers in a basket weave pattern dress up the intersection while contrasting gray pavers identify crosswalks.

To reflect the symmetry of the nearby gatehouses that date back to the 1915 Panama-California Exposition, Caughey positioned large round concrete planters containing a coral tree in front of each gatehouse. When in bloom the deep reddish-orange glow of the coral blossoms brightens up the site. The tandem intervals encircling each planter echo the architectural treatment of the corners of the gatehouses and continue the visual dialogue. The planters also double as signs that identify the plaza. Metal letters mounted on the west sides of the planters spell out Balboa Park and Sefton Plaza respectively in Goudy Old Style, a typeface designed by Frederic Goudy and released by American Type Founders in 1915, the same year that the Panama-California Exposition opened. An appropriate type choice for this traditional plaza in an historic park!

Tribute to Kate Sessions

Caughey also had a hand in designing the tribute to Kate Sessions on the southwestern corner of the plaza. In the center of a concrete terrace stamped with an organic pattern and surrounded by indigenous plants and shrubs stands a 6 ½-foot bronze statue of Kate Sessions by San Diego engineer and sculptor Ruth Hayward. For impact, Hayward made her sculptures 10–15% larger than the people were in real life. At home in this natural setting among trees she’s believed to have planted over a century ago, Sessions is poised to get to work in her beloved park. She has a trowel in her right hand, an aeonium succulent in her left, and a basket of succulents sits on the ground beside her ready to be planted. When the statue was unveiled in April 1998, some of Sessions’ go-to plants were on display in the adjoining beds, including, Echium, Matilija poppy, Rhaphiolepis, Lily of the Nile, and Echeveria, and the Hong Kong orchid trees that still stand just beyond her to the south.

Founders Plaza

Hayward also created the bronze statues across El Prado at Founders Plaza, which was designed by KTUA in 2001 and features a quiet, reflective pond, low seat walls made of natural stone, and includes interpretive signs that describe the installation and identify the donors, designers, and artists who were involved in its implementation. Founders Plaza honors three visionaries who dreamed of a public park that would provide pleasure and recreation for San Diego’s citizens. A statue of George Marston sits near the pond, his hat placed on the stone surface beside him. He’s holding drawings of the California Tower and Dome as if reviewing plans for the upcoming Panama-California Exposition. Alonzo Horton, regarded as the “Father of San Diego,” and Ephraim Morse, who initiated the park preservation, stand nearby studying the site with what appears to be an early twentieth-century surveyor’s transit and tripod. The meaningful objects accompanying the statues help tell the stories of these four historical figures and their relation to Balboa Park.

The two designs offer an interesting comparison. One presents an organic interpretation, befitting a horticulturist and gardener, and the other presents a more structured architectural approach that relates well to the contributions of the three visionaries in developing the park.

Parsons plan abandoned

The 1915 Exposition interrupted the development of Samuel Parsons’ landscape design plan, which anticipated a well-composed tranquil stretch across the three mesas replete with walking trails, shade trees, and intimate ponds. Parsons “opposed putting buildings, statues and other non-natural intrusions in the park,” said Amero. But the buildings came. And so did the statues.

On the way to Sefton Plaza, we passed the modest Redwood Bridge Club and Lawn Bowling Club buildings. Further south towards Marston Point you’ll find the Chess Club, Horseshoe Club, and Fire Alarm Building. And, of course, the Central Mesa is bursting with buildings many of which are left over from the 1915 Exposition, others from the 1935 Exposition, still others have been more recently designed and built, and some are new buildings currently under construction.

Coolest spot in the West Mesa

Before we leave the West Mesa, I want to point out an astonishing grove of between 40–50 magnificent Magnolia trees just beyond Sefton Plaza and the south gatehouse on the east side of Balboa Drive. It’s truly the shadiest and coolest spot in the West Mesa! And on the other side of this Magnolia copse is a pair of towering Eucalyptus trees and a quartet of monumental Bunya pines, the scale of which is staggering. It’s a relaxing spot for lunch on the lawn. Or you can continue on to Pine Grove picnic area.

Marston Point

If you do go all the way to Marston Point, the southernmost edge of the West Mesa, you’ll see some of the remaining California pepper trees with their gnarly trunks and feathery leaves scattered about, and catch sight of the bay and the rise of downtown. The original entrance into City Park was at Date Street and Eighth Avenue. The entrance was moved north to El Prado (opposite Laurel Street) for the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in order to intersect with the Cabrillo Bridge. Years later, in 1958, Interstate 5 took a big bite out of the southwestern corner reducing the size of the park and leaving Elm Street as the current southern boundary.

As you venture south, be prepared to find yourself directly under the flight path around Hawthorne Street as overhead planes continue their descent into San Diego International Airport. Otherwise, from Sefton Plaza head eastward past the gatehouses, past Nate’s Point Dog Park, and across the Cabrillo Bridge into the Central Mesa.

Have a great question? Submit questions directly to SDDW presenters here!

About Susan Merritt

Susan Merritt researches and writes about visual communication, material culture, and design history. She completed postgraduate study in graphic design at the Basel School of Design and earned an MA in Design Research, Writing and Criticism from the School of Visual Arts. She is Professor Emerita of SDSU's School of Art + Design where she taught graphic design and graphic design history while maintaining a professional practice. Merritt is a founding member of AIGA San Diego and contributing writer to AIGA’s Eye on Design blog. She and husband Calvin Woo co-founded Design Innovation Institute, which fosters traditional and non-traditional areas of design and supports student scholarships. She sits on San Diego Design Week’s advisory board and is an active member of the steering committee.

Design Innovation Institute | Facebook | Instagram | Writing