About the Event

Experience the San Diego skate scene through the lens and words of J. Grant Brittain, whose iconic photography documents its inception throughout the region in the late 1970s and early 1980s and continues to the present day. A short film on his career by New York-based artist and director Mac Premo has also been newly released here.

VIDEO: J. GRANT BRITTAIN 20/20 BY MAC PREMO

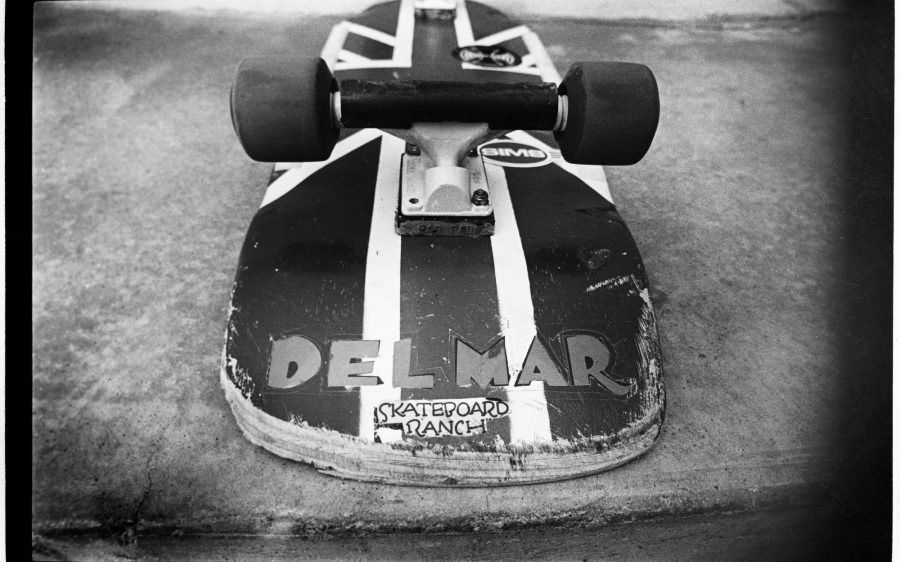

The Del Mar Skate Ranch Is Where It All Began

The popularity of skateboarding was booming when the Del Mar Skate Ranch opened its gates in August, 1978, and I was one of its many employees. I lived in Cardiff-by-the-Sea, and happened to live next door to a pro skater, Tom “Wally” Inouye, who told me he was helping to design a new skatepark in Del Mar and wanted to know if I needed a job. I jumped on it.

After working there a few months, I began to take notice of the skate photographers coming through the park with the pro skaters, and then I’d see their photos a few months later in Skateboarder and Skateboard World Magazines. I was an art student at Palomar College, and I was intrigued by what they were capturing on film. One day, in February, 1979, I borrowed my roommate’s Canon AE-1—he loaded the film for me, and I shot a roll of local skater Kyle Jensen. I turned the roll of Kodachrome 64 in at a local camera store, and after it was processed, I opened the box and was amazed that two of the color slides actually turned out. I had exposed the film correctly, focused the lens, and captured the action at the peak moment. I was stoked and hooked on my new hobby.

Shortly after borrowing that camera, I bought a used Minolta SRT201 and started shooting my friends and local skaters with black and white film, which was the cheapest, since I had no money. I would sneak out during work and shoot anyone that could get above pool coping. Eventually I would get brave enough to shoot a pro skater or two, even if they didn’t know I was there. After a year and a half, my friend Sonny Miller took me into the darkroom at Palomar College, and I finally printed my first negative. I distinctly remember that first print coming up in the developing tray and having that life-changing moment. I had found my new love, my new path, and my future vocation. I knew photography would never not be in my life. I dropped my art classes and enrolled in three photography classes, and I was on my way.

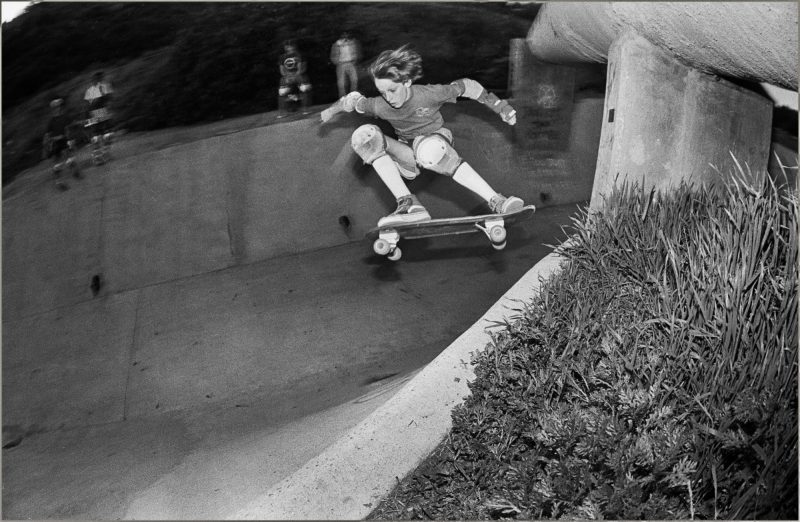

I always say that I was in the right place at the right time. The Skateboarding Boom died shortly after I started shooting photos, and a lot of the skateparks were bulldozed—the Del Mar Skate Ranch was pretty dead but somehow stayed open. The locals and pros kept coming, and there were still skate contests, and I kept shooting away and honing my photo skills for the next couple of years. I was at the right place at the right time in 1983 to help found Transworld Skateboarding Magazine and help build its success as its photo editor and senior photographer. TWS allowed me to leave my job as the manager of the skatepark in 1984 and shoot skateboarding fulltime — traveling the world and helping TWS show skateboarding to a global audience. After leaving my employment at the Del Mar Skate Ranch, I continued to shoot photos there until it closed in 1987 due to the cost of insurance — a sad day. It too was bulldozed after that, and skateboarding took to the streets and backyards, and skateboarders adapted to a new world. I look back at the photos of the Del Mar Skate Ranch that I shot over that time, and I realize that my life would be much different had I not worked there and picked up a camera.

This selection of photos are some of my favorites of those I shot during my time at the Del Mar Skate Ranch. The park once stood at Surf and Turf Recreation, between the miniature golf course and the Tennis Club, on the west of I-5.

- J. Grant Brittain

A Legendary Skate Spot

Sanoland has been a pretty famous skate spot since the 1970s, but you probably don’t know of it, even though you might pass by it several times a week in your commute on I-5 through Cardiff-by-the-Sea.

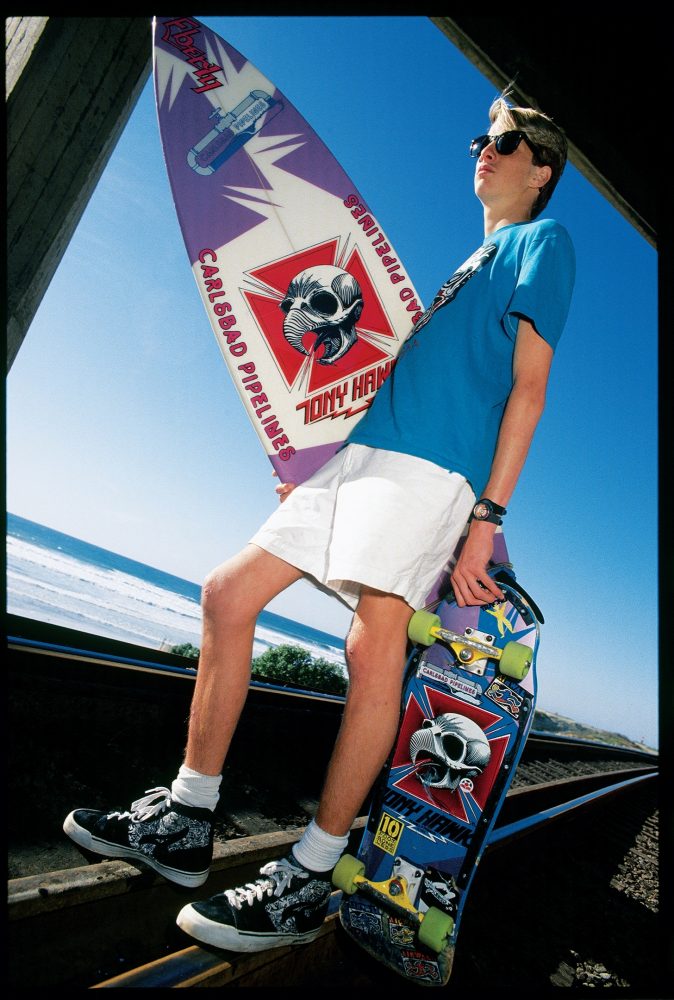

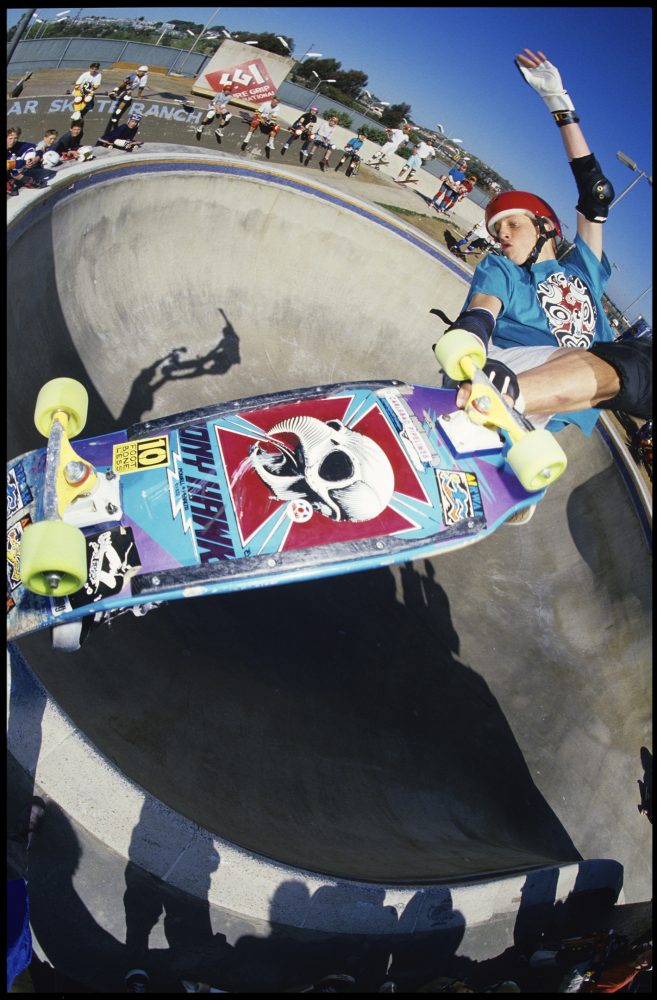

Recently, to commemorate Tony Hawk’s joining the Vans Shoes Skate Team, we recreated a couple of classic 1983 photos that I shot of Tony back then. You might have thought to yourself, “What took so long?” You’re not the only one asking that question—it is, after all, a pretty natural pairing of a great skateboarder and a great product. Tony is probably the best and most respected skateboarder who ever lived, and he would be a great ambassador for any company. Vans is one of the oldest and most reliable fixtures in skateboarding, with an unwavering commitment to the lifestyle and sport.

Don’t even think that this is Tony’s first time wearing Vans. In his early years, right after he first stepped on a skateboard, his feet were usually in Vans. I have photographed Tony since 1980, and during the first six years I shot him he wore Vans in most of the photos. Back in those early times, a skater would try to get as much longevity as they could out of a pair of shoes, and Shoe Goo and Duct Tape helped prolong a pair’s life. Skating delivers quite a beating. Young Tony was no different in trying to make a pair of shoes last, and the shoes he wore in a variety of the photos we took together are in different stages of wear and tear and decay, but in spite of that, his skating never disappointed.

In 1983 Tony lived at the Cardiff Cove condos with his family, near the end of the skateable mile-long concrete structure. In the early 1980s, we Del Mar Skate Ranch locals would meet up now and then, session the rugged banks, and shoot photos. The Sanoland trench ran parallel to the Interstate 5 freeway, and at the top section there was a small drainage pipe that started on the other side of the freeway, ran beneath it, and emptied out into Sanoland. Skaters would sit or lie down on their boards and bomb the pipe at speed from the top entrance, riding towards the light at the end of the tunnel. Once exiting the pipe and entering the ditch, they would carve the walls the rest of the way down.

The portrait that I took of Tony in 1983 shows him sitting on his board at the end of the pipe, looking at me and my Minolta camera and holding still for a quick snapshot. I didn’t plan to shoot it — I just did.

Well, 37 years later, Tony and I went back to Sanoland (we both live only ten minutes from it) and shot a new portrait, mimicking the original one the best we could. After taking the portrait, we reshot some action shots on the banks, recreating some that we shot back in 1983. It’s interesting to see in the images that even as he changes from a teenage boy into a fifty-plus-year-old man, you can still always see that young skate rat inside.

I have included several shots of Tony and other friends skating over the years here for your viewing, and I encourage you to search Sanoland out while it’s still there—we’re losing spots like this daily to progress. Here’s a hint to Sanoland’s location, it’s west of I-5 in Cardiff-by-the-Sea.

Enjoy!

- J. Grant Brittain

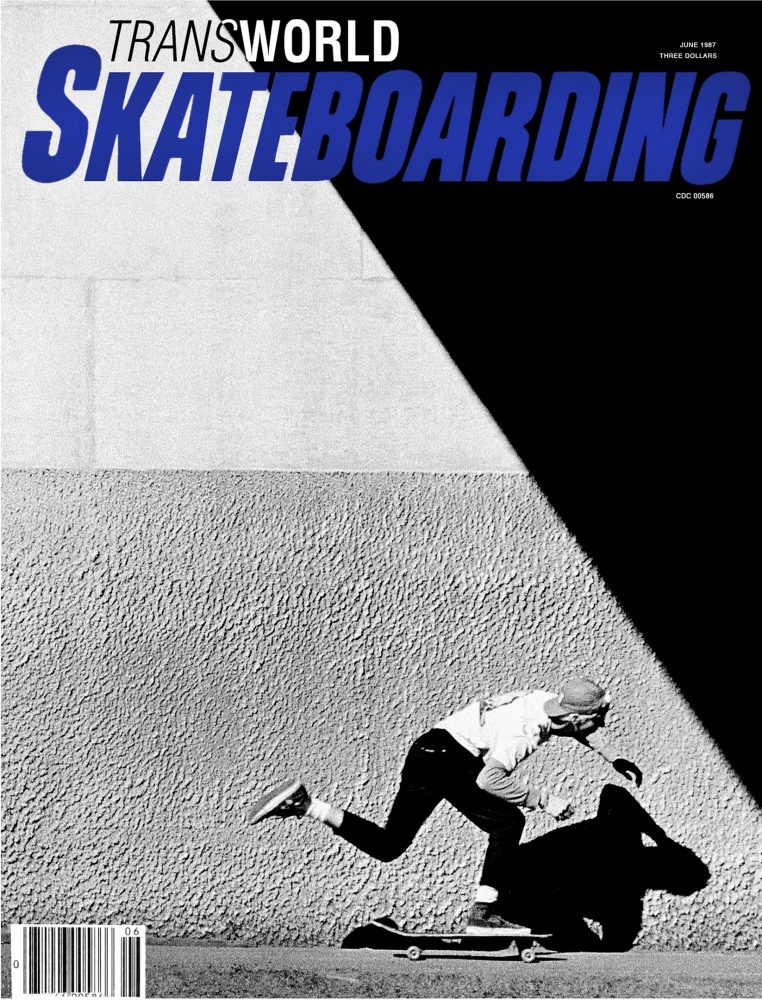

The Story Behind The Push (and How it Almost Didn’t Become a Classic Skateboarding Magazine Cover)

In late 1986, I would drive east on Via de la Valle, in Del Mar, and pass beneath the overpass of the I-5 freeway on my way to get coffee at The Pannikin. As a photographer, I was always on the lookout for a good photo or background, and I had long admired the shaft of light that shone through the gap in the bridge above, a gap which was between the north and southbound lanes and bisected the ferroconcrete wall below with contrasting shadow and light.

I am often asked, “Do you see in black and white?” The answer is “Hell yes, a lot.” There are certain scenes that scream black and white, and this simple geometric shape cast by the sun onto the massive backdrop was projecting strongly onto my photo brain. I started to previsualize a photograph of a skateboarder passing in front of the textured wall, and I began to calculate what time of day to shoot it. Over the next few days, I would see the angle of light change daily as the earth revolved. I finally figured that early afternoon would be the best time to capture the shadow’s diagonal shape in my Nikon’s viewfinder.

At this time, I was the photo editor and senior photographer at Transworld Skateboarding Magazine (1983-2003), and Tod Swank, who was a great skater and skate photographer, was my darkroom tech. I enlisted Tod as my photo stunt dummy, and we met up at The Pannikin. We walked over to the shoot location and sussed out the light situation—it looked pretty good. Once I took up position on the opposite side of the four-lane road, I directed him by shouting commands and waving my arms wildly. There was quite a bit of traffic, and we had to wait for a break in the cars going by. Tod pushed back and forth on his board, doing a variety of maneuvers, some pretty comical, including one in a Superman stance. I ran two rolls of Kodak Tri-X 36-exposure film through my camera and felt like we had something usable. We’d captured what I’d envisioned.

Let me point out that this was not shot specifically for the cover — that idea came after we developed the film in the darkroom — I just wanted to have a photo for the mag. Tod developed the film and gave it to me with a contact sheet, and I placed it on my light table and squinted through my magnifying loupe. One image stood out—the frame with Tod simply pushing along the sidewalk. It was so basic — it was the foundation of skateboarding, it was the first thing we all learn to do after stepping on a board, it was the essence of this activity we who do it love. We all have this in common: we push.

I showed the chosen frame to David Carson, who was the art director — later to go on to become a design guru — and he was stoked on it. He suggested it for the cover of TWS, and I thought this was a great idea. David also thought that the cover should be designed without any Day-Glo cover blurbs, which were common on New Wave-style 80s covers, that would muck up the clean design and crowd the pushing skater out of the frame. This would be the perfect cover to go with Garry Scott Davis’s article “Soul Power,” which was scheduled for the June 1987 issue. This photo seemed to us to be the Everyman/Everywoman skate photo: everyone could relate to it, and it said soul power big-time! That’s what we thought, but what you think isn’t always what others will think. We presented the design at an editorial production meeting, and the rest of the staff hated it. It broke all of the magazine distribution and skateboarding world rules — it had no Day-Glo cover blurbs, it was shot in black and white, and it showed a non-pro skater. It wasn’t a guy-in-the-sky peak action shot of a skater on a logoed-out skate deck. I was a bit surprised by the response of the other staff members, and the meeting got more and more heated. After the meeting ended, I retreated to Carson’s office and tried to come down from it. I pretty much thought our Push cover was a dead design idea after that argument, and I was pissed!

I stayed away for a couple of days to cool off. Eventually, I went back to the office, and the June 1987 issue came out miraculously (I don’t know how it was approved or by who), with the Carson-designed Tod Swank cover. The photo caption on the contents page read, “It doesn’t matter who, where or what. It’s just a skateboarder… skateboarding. Photo: Brittain”. That was what it was all about! It didn’t matter that it didn’t have Swank’s name — that was the point — it was any skater! For the record, Tod didn’t mind not having his name on the cover photo.

You would think that the commotion would have all ended there, all hunky-dory, right? Not quite. Just as many of our Skate readers hated it as liked it. Friends told me later that they hated or didn’t get it, and wondered what the hell we were thinking. I tried to explain it to those people, the every-skater photo thing, the feeling of freedom through the simple act of pushing down the street—you know … that thing we all do—but it was a hard sell.

The mag took some heat for a long while, but I started to notice skateboard mag covers changing over time. I think the Push cover opened up some thoughts on what could go on a skate mag cover, and made it clearer that you didn’t have to stick to newsstand consultant rules. After all, we’re skaters — we don’t need no stinkin’ rules! People warmed up to that Push cover after twenty or so years. I even heard the old haters say that it was one of their favorite covers, and even one of their favorite skate photos. It’s that old saying, “Time will tell” — well it did in this case.

Now, in 2020, I regale young skaters with the story of the Push cover almost not being a cover and the reasons, and they are amazed, because as a cover it would be so tame by today’s standards. I am proud of that.

If you want to see where we shot it, it’s under the intersection of the I-5 freeway and Via de la Valle Avenue in Del Mar.

- J. Grant Brittain

Have a great question? Submit questions directly to SDDW presenters here!

About J. Grant Brittain

J. Grant Brittain is an accomplished photographer who helped found Transworld Skateboarding Magazine in 1983. For over 20 years he served as its only Photo Editor and as a Senior Photographer. His dynamic skateboarding photos shot all over the world were on 60+ covers over that time. He went on to help start The Skateboard Mag, but is now focused on his own artistic, commercial, and personal projects: Teaching photography, doing photo exhibits all over the world, releasing new photos from his 40 year archive, and is currently finishing up his book project. Grant is a lifelong North San Diego County native and lives in Encinitas with his family and his pets.